New to SLOs

New to SLOs? You're in the right place.

Learn how SLOs can transform reliability, empower your teams, and make your users happier,

all right here with Nobl9.

Why SLOs?

Every tool promises full visibility. And to be fair, they deliver it. You get uptime charts, latency percentiles, MTTR dashboards, trends, alerts, traces… all of it.

But knowing what’s happening isn’t the same as knowing what matters.

With so much information, and no central control panel, it’s easy for things to slip through the cracks. You’re drowning in detail. Without a way to define what good looks like, reliability becomes a never-ending stream of noise. Everything looks important. Nothing is prioritized. And even when the system is “up”, your users still might be having a terrible experience.

Intent and organization is missing from these systems. SLOs are a great way to manage the flood of data.

The Basics

-

What's an SLO?

What's an SLO?

-

What's an SLI?

What's an SLI?

-

What's an Error Budget?

What's an Error Budget?

A service level objective (SLO) is a performance target. It answers the question, “How good does this service need to be, and how often?”.

That might mean:

- 99.9% of login requests succeed within 300ms over 30 days

- 95% of data refresh jobs complete within 15 minutes

- Less than 0.1% of search queries return an error per week

An SLO is a goal. A line in the sand that helps your team decide what’s acceptable, what needs attention, and what can wait. As both your software and environment shift and change often, so should your SLOs. Good SLOs are meant to be iterated on as circumstances change.

A service level indicator (SLI) is a raw measurement of how a service is performing. It’s a single, observable metric like availability, latency, or error rate, and it’s often pulled from telemetry systems.

Think of it as the evidence.

Examples of SLIs:

- Percentage of successful HTTP responses

- Average response time for a checkout API

- Rate of failed background jobs

An SLO uses one or more SLIs to define a target. If your SLI is "successful checkouts per request”, then your SLO might be: "99.5% of checkouts succeed over 30 days."

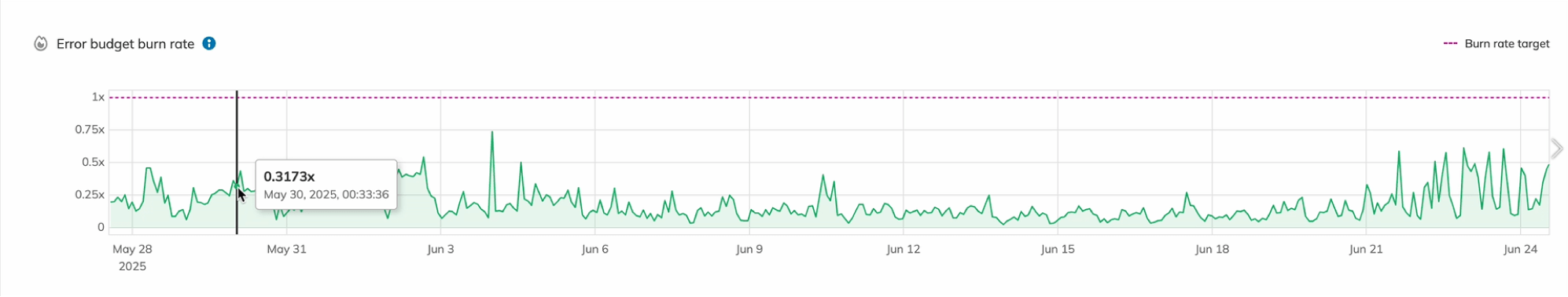

An error budget is the margin for failure you’re allowed based on your SLO.

If your SLO is 99.9% success, that means 0.1% of failures are allowed over a specific time window. That’s your error budget. It’s how you manage risk intentionally instead of emotionally, and it’s how you tell when to prioritize stabilizing reliability on critical services.

Error budgets let teams take calculated risks, like shipping faster or holding off on low-priority incidents, because you know how much room you have before reliability, and the customer experience behind each service is at risk.

How SLOs fit into Modern Reliability Management

Modern software systems are messy. Today’s applications are rarely standalone - they’re stitched together from dozens of internal services and external dependencies, each owned by different teams, each shipping changes on their own schedule. This is part of what makes SaaS so powerful: every component is built to do one job well. But the more interdependent everything becomes, the harder it gets to understand how the system is actually performing.

One change in a downstream service can ripple through multiple teams. A slow response time on one API can quietly degrade the entire customer experience. When everything is connected, knowing what’s going on - and what matters - becomes a math problem with too many variables.

Modern software is built on chains of dependencies. One service calls another, which depends on a third, which runs on a platform managed by someone else entirely. That complexity isn’t a bug - it’s the whole point of composable architectures. Each part is designed to move fast and operate independently.

But when every team monitors reliability in their own way - with different tools, different definitions, and different thresholds - there’s no shared understanding of what “working” even means. Metrics are siloed. Alerts are uncoordinated. Teams are reacting to symptoms in isolation, not solving problems together.

You can’t manage what you can’t see. And you definitely can’t align a company around reliability if everyone’s measuring it differently.

Knowing what’s happening isn’t the same as knowing what matters.

When they promise you full visibility, they are probably delivering that to you, and more, with the mountains of dashboards, trends, metrics, alerts, and forensic views. They give you so much to sort through that it almost becomes meaningless. It’s a basement or attic full of stuff, but also mysteries unless you’ve seen the infrastructure from the start.

Every tool promises full visibility. But most of the time, visibility doesn’t mean you know what the hell is going on.

You’ve got dashboards full of metrics - MTTR, availability, percentiles, latency. Alerts firing left and right. You’re reacting fast, sure. You can see everything. But with that much information, it all starts to blur.

SLOs bring context

They help you cut through the noise and figure out what actually matters.

What to work on next.

What that feature release will mean for stability.

Where your KPIs connect - or don’t connect - to the customer experience.

And how your team should invest in reliability going forward.

As systems grow more complex, teams need better ways to understand how well their services are performing.

Dashboards full of uptime, latency, and MTTR metrics give you lots of information, but not always insight, especially when it comes to what users actually experience.

Service level objectives, or SLOs, are performance targets. On their own, in a vacuum, they’re exceedingly simple: a goal for how often something should work. However, when used well, they help teams define what reliable means in context. They create clarity across engineering, product, and leadership and help teams align on where to invest, when to respond, and how much risk is acceptable.

SLOs aren’t new, but they’ve become essential as teams grapple with managing reliability in the most efficient way possible. As adoption increases, teams are asking harder questions:

How do we make them work across teams?

How do we connect them to business priorities?

And what happens when the first version doesn’t deliver what we expected?

Let’s break it down…

The SLO Paradox

Anyone who understands modern reliability practices agrees on one thing: SLOs are the right way to manage service health. They're outcome-focused, grounded in user experience, and provide a common language across engineering, operations, and business stakeholders.

But the moment you try to implement SLOs at scale,

the whole thing becomes... a mess.

It’s not that people don’t want SLOs.

It’s that they try to implement them in spreadsheets, YAML files, or point solutions that lack consistency and structure. Initiatives stall. Teams abandon efforts. Or, worse, poorly implemented SLOs create more noise and complexity than they solve.

Mismanaged SLOs are worse than no SLOs at all.

They create false confidence, alert fatigue, and political friction. They add cost without clarity. And they bring teams right back to firefighting… but now with even more dashboards.

The False Promise of SLOs-as-a-Feature

Nearly every monitoring or observability platform now claims to support SLOs. And in some basic sense, they do. You can point a template at your latency metrics, define an objective, wire up an alert, and call it a day.

But here’s what we hear over and over again:

“We tried SLOs. It was a lot of effort, and they didn’t really help.”

That failure usually isn’t about SLOs themselves. It’s about how they were implemented.

In most cases, the tools or techniques used to implement SLOs didn’t meet the requirements of the job to make them useful.

These platforms bolt SLOs on as a feature, not as a foundation. They treat reliability as a visualization problem. But tracking metrics isn’t the hard part. You get plenty of that from these same systems. The hard part is designing a consistent, scalable, and meaningful system that connects reliability goals to actual engineering and business decisions.

Eventually, the dashboards get ignored. The alerts get muted. The “SLO initiative” loses momentum and fades into the background.

It’s not that the idea didn’t work.

It’s that the environment it was deployed in wasn’t built for it.

-1.png)

.png?width=1200&height=628&name=Building%20Reliable%20E-commerce%20Experiences%20(42).png)

.png?width=1200&height=628&name=Building%20Reliable%20E-commerce%20Experiences%20(34).png)